9 December 2021. With the election of Olaf Scholz as Chancellor, the new German federal government consisting of the SPD, the Greens and the FDP has officially begun its work for the next four years. The core points of the cooperation are summarised on 177 pages in the coalition agreement. I am very pleased that the coalition of the three parties clearly commits itself to the space sector. The coalition agreement states that New Space and the space sector as a whole are "central technologies of the future". It also states that a new German space strategy is to be developed, which I of course very much welcome. In the new coalition, the Federal Ministry of Economics will continue to be responsible for the space industry, but now under the leadership of Robert Habeck of the Greens. As a result, the issue of sustainability will play a much greater role, for example in the role of the space sector for climate protection or in the important task of avoiding additional space debris – be it through greater investment in the development of reusable rockets or through technologies that help eliminate already existing space debris or avoid producing it in the first place.

Space debris is becoming more and more of a problem

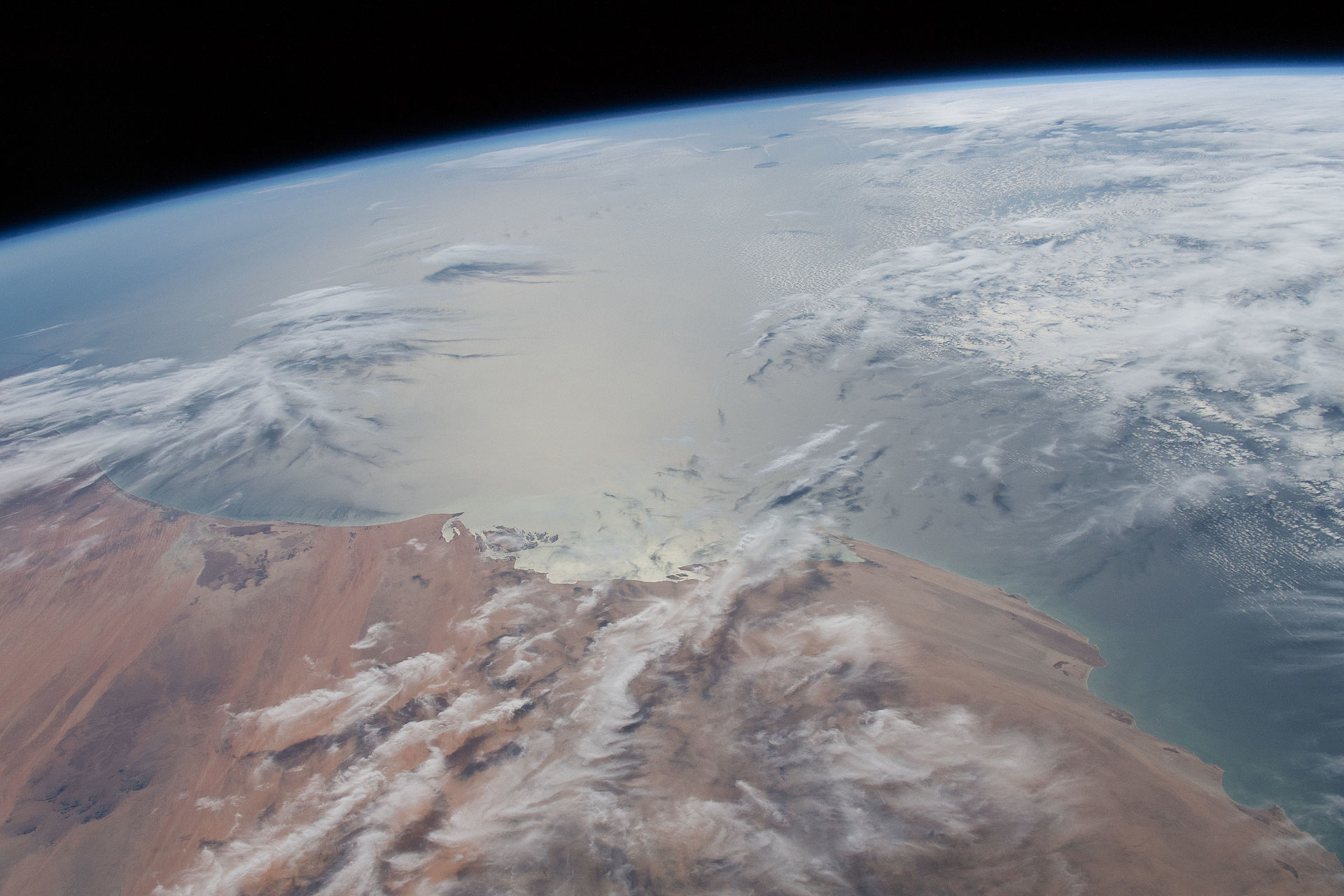

Space debris is a growing problem because it is becoming more and more of a danger to the space infrastructure in various orbits. An incredible 8,500 tonnes of space debris are already orbiting the Earth; satellites sometimes have to fly evasive manoeuvres on a daily basis or are hit by tiny debris objects that cannot be detected by radar. And in the next few years, the number of satellites will continue to increase, especially in low Earth orbit, due to so-called constellations, i.e. swarms of thousands of satellites. I therefore think it would be a good idea for the international community to agree on common rules for the usage of space. And this includes not only the question of how space debris can be avoided or minimised from the outset, but also the question of respectful and above all prudent interaction with one another.

Satellite shoot-down as a demonstration of power

The fact that I have to talk about respect and prudence unfortunately has a less than pleasant reason. In mid-November, Russia shot down a derelict reconnaissance satellite with a so-called anti-satellite rocket creating more than 1,500 pieces of debris. These now add to the dangerous cloud of debris that is hurtling around the world. The USA, China and most recently India also demonstrated that they could use these anti-satellite weapons. That Russia is making this show of force while its own cosmonauts are stationed on the ISS was a nasty surprise to me. The ISS crew even had to briefly retreat into the emergency capsules out of concern about a possible collision with debris.

I was shocked by this form of sabre-rattling – which in my opinion would not have been necessary at all, because it is widely known that Russia has anti-satellite weapons. I would have liked us to get over this geopolitical strong-arming in international cooperation, especially in space. After all, many players have now realised that space must be used on a basis of cooperation – and further space debris only makes this task more difficult.

But Russia apparently deliberately wanted to send the message to the world that it can shoot down satellites, and thus any satellite they want to hit is in danger. For me, as CEO of a space company whose core business is building satellites, this is a disturbing idea. And I have the feeling that a new Cold War in space is already underway again. There is no other way I can explain such a deliberate provocation. The implication is that this could seriously threaten the infrastructure in space. This would have serious consequences for everyday life on Earth – especially for logistics, the financial system and energy networks. All these core areas of the global economy would be disrupted or even shut down.

Guidelines and recommendations are needed for dealing with infrastructure in space

It is therefore high time that the international community agrees on rules for dealing with infrastructure in outer space. The European Union has set a good example in this regard. Since the beginning of 2021, a European consortium of 15 companies and institutions, including OHB, has joined forces in the Spaceways project. The consortium's task is to develop guidelines and recommendations on how the players can share the orbit as sustainably as possible and, above all, in a structured manner. The EU speaks of Space Traffic Management, which nicely describes the core of the topic: in the end, as in road traffic regulations, it is about finding a common understanding of rules for traffic in space. The consortium's work is due to be completed by mid-2022.

However, the case of the Russian satellite shoot-down also shows that a set of rules created only by Europeans will not be enough. Sure, it is always good when a group of states sets a good example. However, a global agreement will be necessary for a sufficiently high level of security. I very much hope that the various players will join the EU initiative, given the promising profits from future satellite applications.

Personal details:

Born in 1962, Marco Fuchs studied law in Berlin, Hamburg and New York. He worked as an attorney in New York and Frankfurt am Main from 1992 to 1995. In 1995, he joined OHB, the company that his parents had built up. He has been Chief Executive Officer of OHB SE since 2000 and of OHB System AG since 2011. Marco Fuchs is married and has two children.