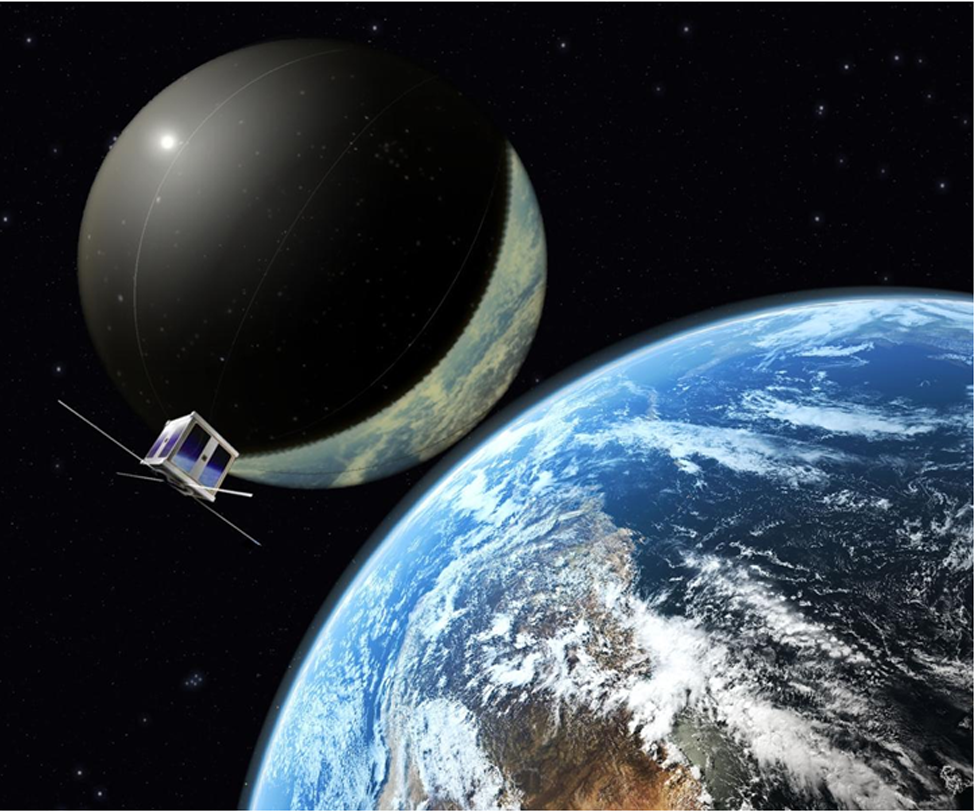

There’s quite a lot going on up there: space debris is becoming an ever bigger problem

“It would be nothing short of a catastrophe if we were no longer able to launch any missions into orbit because of all this scrap” / The Space Debris Center of Competence at OHB is looking into ways of avoiding space debris

The Space Debris Center of Competence at OHB has been providing support for a year and a half now, offering its experience and analyses for the reduction of space debris. A further goal pursued by the Center is to enhance OHB’s processes in order to avoid space debris as far as possible. This also includes the installation and maintenance of a knowledge database. In an interview, Dr. Charlotte Bewick, the coordinator of the Space Debris Center, talks about the hazards posed by space debris for spacecraft and humans and the contribution OHB is making to reducing it.

Space junk – why do we even care about it? Isn’t it far enough away?

Dr. Charlotte Bewick: Space debris, human made junk in orbit, can pose a great hazard because the particles could hit astronauts, satellites and other spacecraft and damage them.

How much junk is floating around up there?

Bewick: There are certain orbits that are quite contaminated. Especially at altitudes of 700 to 800 kilometers, where there is hardly any atmosphere to low down orbiting objects. This means that satellites and fragments remain at these heights for hundreds or even thousands of years. At the same time, many satellites are located in this area, as it is particularly useful for Earth observation missions. Below 400 km, scrap particles burn up within a few years when they enter the earth’s atmosphere.

What are the options for eliminating space debris?

Bewick: You can ensure a uncontrolled re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere by either constructing the satellite in such a way that it enters and burns up in the earth’s atmosphere virtually by itself at the end of its life, or you can perform a special manoeuver. For my doctoral thesis I also worked on re-entry methods for smaller satellites with the help of the solar radiation pressure and the air resistance of the residual atmosphere. We are also exploring these propellantless re-entry techniques with particular interest at the Center. At the Space Debris Center, we advise OHB’s project teams on how certain guidelines can be adhered to in satellite production in order to prevent even more space debris from being generated by our satellites.

So there are rules that can be followed to avoid space debris? Explain ...

Bewick: Of course, there is ISO 24113 and the standard of the European Cooperation for Space Standardization (ECSS). The rules set out the ISO standard are effectively our 10 commandments and define the primary requirements for the avoidance of space debris. The ISO standard also states that satellites in low earth orbits are only allowed to stay in orbit for 25 years. We at the Space Debris Center use special software to calculate whether the satellite will re-enter the earth’s atmosphere on its own after 25 years or whether we need a maneuver. During production, we can make sure that materials with a certain melting point that burn more easily are used. If a maneuver is necessary, there are also other aspects to consider: we will need more fuel and hence larger tanks, nozzles and much more.

Do you also know the places where there is a lot of debris so that satellites assembled by OHB can avoid it?

Bewick: There is, for example, DISCOS, the space debris database of the European Space Agency ESA. And the amount of space debris is growing all the time. It would be nothing short of a catastrophe if we were no longer able to launch any missions into orbit because of all this scrap since we would then lack important knowledge and life on earth would no longer be imaginable without satellite technology.

Catastrophes? Oh dear! Have there been any yet? Any crashes in space?

Bewick: Unfortunately, there have. The collision of the Kosmos 2251 and Iridum 33 communication satellites almost exactly ten years ago at an altitude of almost 800 kilometers is particularly well know. The speed at which the two satellites had been traveling caused a huge cloud of dust with more than 100,000 individual pieces when they collided.

Spectacular! Have there been any other similar events in the past?

Bewick: We also know that China deliberately launched a defective Chinese Fengyun series weather satellite to show that they were able to do so. Using a rocket, the Chinese destroyed the satellite in 2007 from the ground, breaking it up into over 40,000 pieces of debris that were thrown into various orbits.

So, there’s quite a lot going on up there. You must have your hands full at the Space Debris Center.

Bewick: That’s right. On the one hand, we advise the teams on the rules and regulations concerning space debris so that they can make design decisions at an early stage, plan disposal maneuvers for our satellites and calculate how long they will survive in orbit or what happens during re-entry.

Why is the re-entry so interesting?

Bewick: Most components we use in satellites burn-up during re-entry. However, there are some units of equipment which consist of materials with a high melting point such as brackets made of Titanium alloy, propellant tanks and the lenses and mirror of our optical instruments. For these we have to conduct complex simulations to compute where they are likely to land and with which kinetic energy in order to be able to reduce the risk of damage and injury. Also in this subject there are strict rules that we have to adhere to. In several technology studies we are researching new materials and methods to further reduce the number and mass of objects surviving re-entry.

If you take a look into the future, what will we need to solve the problem?

Bewick: What we need is an orbital towing service. There are already many interesting studies and mission drafts for such a "space-tug". However, nobody currently wants to pay for such a mission in full as space debris removal is unfortunately not as prestigious as the big scientific research mission missions. The international community must sit down together and find a joint solution. It’s time to act.